From ancient times until the present generation, there have been nations great in might and wealth and extent, but with a heart as small as the paltry amounts owed by its debtor citizens whom they keep behind iron bars for payment default. Such nations will keep a man locked up for years and deny him contact with his family if he owed someone even just a cent and is unable to pay it back. That’s a fact affirmed by one great Teacher.

‘Before you are dragged into court, make friends with the person who has accused you of doing wrong. If you don’t, you will be handed over to the judge and then to the officer who will put you in jail. I promise you that you will not get out until you have paid the last cent you owe.’1

In ancient Greece, bankruptcy did not exist. If a man owed and he could not pay, he and his wife, children or servants were forced into ‘debt slavery’, until the creditor recouped losses through their physical labor.

Bankruptcy is also documented in ancient East Asia. According to al-Maqrizi, the Yassa of Genghis Khan contained a provision that mandated the death penalty for anyone who became bankrupt three times.

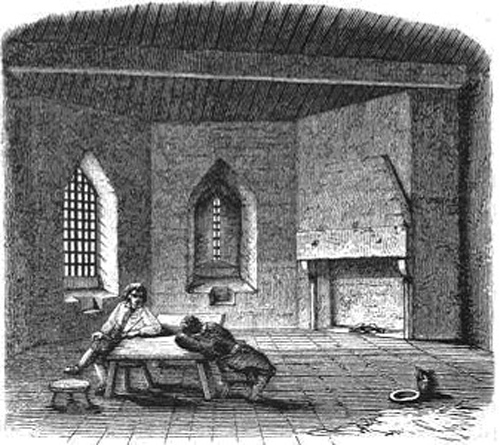

During Europe’s Middle Ages, debtors, both men and women, were locked up together in a single large cell until their families paid their debt. Debt prisoners often died of diseases contracted from other debt prisoners. Conditions included starvation and abuse from other prisoners. If the father of a family was imprisoned for debt, the family business often suffered while the mother and children fell into poverty. Unable to pay the debt, the father often remained in debtors’ prison for many years. Some debt prisoners were released to become serfs or indentured servants (debt bondage) until they paid off their debt in labor.

In UK, until imprisonment for debt was abolished in 1869, life in the debtors prison was a miserable experience, and the inmates were forced to pay for their keep. Samuel Byrom, son of the writer and poet John Byrom, was imprisoned for debt in 1725, and in 1729 he sent a petition to his old school friend, the Duke of Dorset, in which he raged against the injustices of the system:

‘What barbarity can be greater than for jailers (without provocation) to load prisoners with irons, and thrust them into dungeons, and manacle them, and deny their friends to visit them, and force them to pay excessive fines for their chamber rent, their victuals and drinks; to open their letters and seize the charity that is sent to them! And when debtors have succeeded in arranging with their creditors, hundreds are detained in prison for chamber-rent and other unjust demands put forward by their jailers, so that at last, in their despair, many are driven to commit suicide…law of imprisonment for debts inflicts a greater loss on the country, in the way of wasted power and energies, than do monasteries and nunneries in foreign lands… Holland, the most unpolite country in the world, uses debtors with mildness and malefactors with rigour; England, on the other hand, shows mercy to murderers and robbers, but of poor debtors impossibilities are demanded.’ (Manchester Times, 22 October 1862)

That letter would be still very relevant to many of the leaders of the nations where debtors’ prisons still exist.

Dr Samuel Johnson almost landed in a debtors’ prison in England for not being able to pay a trivial amount.

‘He [Dr Samuel Johnson] was arrested for debt. The man who was the ‘chief glory’ of his age, whose life had been laborious and frugal, could not pay five pounds eighteen shillings. It was by the benevolence of Richardson the novelist that he was saved from that ‘picture of hell upon earth’, a debtors’ prison.’ From the introduction to The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abyssinia.

Modern Debtors’ Prisons

In modern times, several countries still practice the primitive and inhumane system of sending debtors to ‘hell upon earth’.

Greece still practices it, with one change; imprisonment for debts to the government was declared unconstitutional in 2008. Imprisonment, however, is still retained for debts to private banks.

Other prominent countries which still practice to the full extent this ancient system of sending debtors to prison are the United Arab Emirates and China. Hong Kong has long imprisoned debtors from its tradition as a British colony. The first mainland prison sentence for unpaid debts was handed down in 2008. Life imprisonment is possible for non-repayment of debts incurred with ‘malicious intent’.

‘Debtors in the United Arab Emirates, including Dubai, are imprisoned for failing to pay their debts. This is a common practice in the country. Private banks are not sympathetic to the debtors once they are in prison so many just choose to leave the country where they can negotiate for settlements later. The practice of fleeing UAE to avoid arrest because of debt defaults is considered a viable option to customers who are unable to meet their obligations.’ Wikipedia

At present a comparable concept to debtors prison still exists in various forms in Germany. A maximum six months of ‘coercive arrest’ is still practiced for refusal of payment or fine.

In UK, debtors can still be sent to jail for upto six weeks if they had the means to pay their debt but did not do so.

More than a third of US states allow debtors to be jailed for non payment. A year long study released in 2010 of fifteen states with the highest prison populations by the Brennan Center for Justice, found that all fifteen states sampled have jurisdictions that arrest people for failing to pay debt or appear at debt related hearings. To what extent a debtor will actually be prosecuted varies from state to state.

‘In 1970, the US Court ruled in Williams v. Illinois that extending a maximum prison term because a person is too poor to pay fines or court costs violates the right to equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. During 1971 in Tate v. Short, the Court found it unconstitutional to impose a fine as a sentence and then automatically convert it into a jail term solely because the defendant is indigent and cannot forthwith pay the fine in full. And in the 1983 ruling for Bearden v. Georgia the Court ruled that the Fourteenth Amendment bars courts from revoking probation for a failure to pay a fine without first inquiring into a person’s ability to pay and considering whether there are adequate alternatives to imprisonment.’ Wikipedia. Emphasis mine.

Several countries today still practice the primitive and inhumane system of sending debtors to prison.

India’s prevalent bonded labor system, although officially banned, is a severe form of debtors’ imprisonment. Farmers and their families are held in bondage to their landlords for failure to repay loans and forced to work on their creditor’s lands for just the barest means of survival. This bondage usually lasts the entire life of the farmer, and the bondage is then passed on to his children.

In 1976, Article 11 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights came into effect. It states, ‘No one shall be imprisoned merely on the ground of inability to fulfill a contractual obligation’.

May every nation that still sends debtors to prison take deeply to heart this international covenant:

‘No one shall be imprisoned merely on the ground of inability to fulfill a contractual obligation.’

Pappa Joseph

1 Matthew 5:5-26 Contemporary English Version