By Peter Goodchild

Humanity has struggled to survive through the millennia in terms of balancing population size with food supply. The same is true now, but population numbers have been soaring for over a century. The limiting factor has been hidden, but this factor – oil and natural gas, or petroleum – is close to or beyond its peak extraction. Without ample, free-flowing petroleum, it will not be possible to support a population of several billion for long.

‘Drought refugees from Oklahoma camping by the roadside. They hope to work in the cotton fields. The official at the border (California-Arizona) inspection service said that on this day, August 17, 1936, twenty-three car loads and truck loads of migrant families out of the drought counties of Oklahoma and Arkansas had passed through that station entering California up to 3 o’clock in the afternoon.’

Famine caused by petroleum supply failure alone will result in about 2.5 billion above-normal deaths before the year 2050; lost and averted births will amount to roughly an equal number.

In terms of its effects on daily human life, the most significant aspect of fossil-fuel depletion will be the lack of food. ‘Peak oil’ is basically ‘peak food’. Modern agriculture is highly dependent on fossil fuels for fertilizers (the Haber Bosch process combines natural gas with atmospheric nitrogen to produce nitrogen fertilizer), pesticides, and the operation of machines for irrigation, harvesting, processing, and transportation.

Without fossil fuels, modern methods of food production will disappear, and crop yields will be far less than at present. Crop yields are far lower in societies that do not have fossil fuels or modern machinery. We should therefore have no illusions that several billion humans can be fed by ‘organic gardening’ or anything else of that nature.

The Green Revolution involved, among other things, the development of higher-yielding crops. These new varieties, however, could be grown only with large inputs of fertilizer and pesticides, all of which required fossil fuels. In essence, the Green Revolution was little more than the invention of a way to turn petroleum into food.

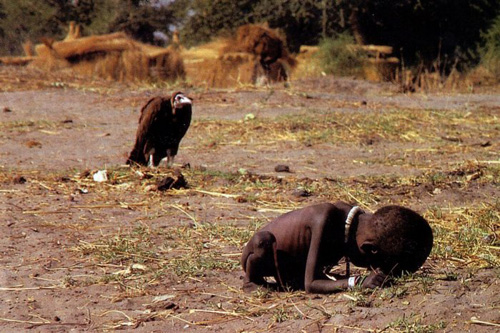

Over the next few decades, therefore, there will be famine on a scale many times larger than ever before in human history. It is possible, of course, that warfare and plague will take their toll to a large extent before famine claims its victims. The distinctions, in any case, can never be absolute: often ‘war + drought = famine’3, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, but there are several other combinations of factors.

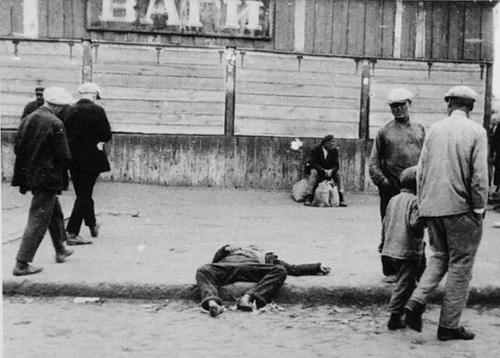

Although, when discussing theories of famine, economists generally use the term ‘neo-malthusian’ in a derogatory manner, the coming famine will be very much a case of an imbalance between population and resources. The overwhelming cause of the imbalance and famine will be fossil-fuel depletion, not government policy (as in the days of Stalin or Mao), warfare, ethnic discrimination, bad weather, poor methods of distribution, inadequate transportation, livestock diseases, or any of the other variables that have often turned mere hunger into genuine starvation.

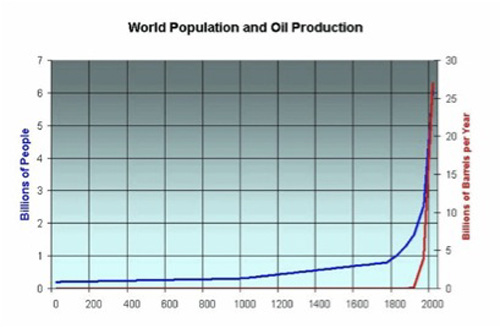

The increase in the world’s population has followed a simple curve: from about 1.7 billion in 1900 to about 6.1 billion in 2000. A quick glance at a chart of world population growth, on a broader time scale, shows a line that runs almost horizontally for thousands of years, and then makes an almost vertical ascent as it approaches the present. That is not just an amusing curiosity. It is a shocking fact that should have awakened humanity to the realization that something is dreadfully wrong.

Mankind is always prey to its own ‘exuberance’, to use Catton’s term2. That has certainly been true of population growth. In many cultures, ‘Do you have any children?’ or, ‘How many children do you have?’ is a form of greeting or civility almost equivalent to ‘How do you do?’ or, ‘Nice to meet you’. World population growth, nevertheless, has always been ecologically hazardous. The destruction of the environment reaches back into the invisible past, and the ruination of land, sea, and sky has been well described if not well heeded. But what is even less frequently noted is that with every increase in human numbers we are only barely able to keep up with the demand: providing all those people with food and water has not been easy. We are always pushing ourselves to the limits of Earth’s ability to hold us.

Even that is an understatement. No matter how much we depleted our resources, there was always the sense that we could somehow ‘get by’. But in the late twentieth century we stopped getting by. It is important to differentiate between production in an ‘absolute’ sense and production ‘per capita’. Although oil production, in ‘absolute’ numbers, kept climbing — only to decline in the early twenty-first century — what was ignored was that although that ‘absolute’ production was climbing, the production ‘per capita’ reached its peak in 19791.

The unequal distribution of resources plays a part, of course. The average inhabitant of the United States consumes far more than the average inhabitant of India or China. Nevertheless, if all the world’s resources were evenly distributed, the result would only be universal poverty. It is the totals and the averages of resources that we must deal with in order to determine the totals and averages of results. For example, if all of the world’s arable land were distributed evenly, in the absence of mechanized agriculture each person on the planet would have an inadequate amount of farmland for survival: distribution would have accomplished very little.

We were always scraping the edges of the earth, but we are now entering a far more dangerous era. The main point to keep in mind, however, is that throughout the twentieth century, oil production and human population were so closely integrated that every barrel of oil had an effect on human numbers. While population has been going up, so has oil production.

Future excess mortality can therefore be determined ― at least in a rough-and-ready manner ― by the fact that in modern industrial society it is oil supply that determines how many people can be fed. An increase in oil production leads to an increase in population, and a decrease in oil production leads to a decrease in population.

In round numbers, global oil production in the year 2008 was 30 billion barrels, and the population was 7 billion. The consensus is that in the year 2050 oil production will be about 2 billion barrels. The same amount of oil production occurred in the year 1930, when the population was 2 billion. The population in 2050 will therefore be about the same as in 1930: 2 billion. The difference between 7 billion people and 2 billion is 5 billion, which will therefore be the total number of famine deaths and lost or averted births for that period.

Passers-by and the corpse of a starved man on a street in Kharkiv during the famine in Ukraine, 1932.

We can also determine the annual number of famine deaths and lost or averted births. From 2008 to 2050 is 42 years. The average annual difference in population is therefore 5 billion divided by 42, which is about 120 million.

It is quite possible, however, that the decline in population will not exactly parallel the decline in oil. In other words, the peak of the population curve may well be a few years later than the peak of the oil curve. People might simply live with less oil per capita for a few decades, i.e. they will just sink further into poverty, with greater problems of malnutrition. In fact, as long ago as 1972, the first edition of The Limits to Growth in its Figure 35, ‘World Model Standard Run’, showed a 40-year gap between the peak production of food per capita and the peak of population7.

Many of those annual 120 million will not actually be deaths; famine will cause a lowering of the birth rate. This will sometimes happen voluntarily, as people realize they lack the resources to raise children, or it will happen involuntarily when famine and general ill health result in infertility4. In most famines the number of deaths from starvation or from starvation-induced disease is very roughly the same as the number of lost or averted births3,4. In Ireland’s nineteenth-century famine, for example, the number of famine deaths was 1.3 million, whereas the number of lost births was 0.4 million. The number of famine deaths during China’s Great Leap Forward (1958-1961) was perhaps 30 million, and the number of lost births was perhaps 33 million.

The ‘normal’, non-famine-related, birth and death rates are not incorporated into the above future population figures, since for most of pre-industrial human history the sum of the two — i.e. the growth rate — has been nearly zero. If not for the problem of resource-depletion, in other words, the future birth rate and death rate would be nearly identical, as they were in pre-industrial times. And there is no question that the future will mean a return to the ‘pre-industrial’.

Nevertheless, it will often be hard to separate ‘famine deaths’ from a rather broad category of ‘other excess deaths’. War, disease, global warming, topsoil deterioration, and other factors will have unforeseeable effects of their own. Considering the unusual duration of the coming famine, and with Leningrad5 as one of many precursors, cannibalism may be significant; to what extent should this be included in a calculation of ‘famine deaths’? It is probably safe to say, however, that an unusually large decline in the population of a country will be the most significant indicator that this predicted famine has in fact arrived.

These figures obliterate all previous estimates of future population growth. Instead of a steady rise over the course of this century, as generally predicted, there will be a clash of the two giant forces of overpopulation and oil depletion, followed by a precipitous ride into the unknown future.

If the above figures are fairly accurate, we are ill-prepared for the next few years. The problem of oil depletion turns out to be something other than a bit of macabre speculation for people of the distant future to deal with, but rather a sudden catastrophe that will only be studied dispassionately long after the event itself has occurred. Doomsday will be upon us before we have time to look at it carefully.

In modern industrial society it is oil supply that determines how many people can be fed.

The world has certainly known some terrible famines in the past, of course. In recent centuries, one of the worst was that of North China in 1876-79, when between 9 and 13 million died, but India had a famine at the same time, with perhaps 5 million deaths. The Soviet Union had famine deaths of about 5 million in 1932-34, purely because of political policies. The worst famine in history was that of China’s Great Leap Forward, 1958-61, when perhaps 30 million died, as mentioned above.

A close analogy to ‘petroleum famine’ may be Ireland’s potato famine of the 1840s, since — like petroleum — it was a single commodity that caused such devastation6. The response of the British government at the time can be summarized as a jumble of incompetence, frustration, and indecision, if not outright genocide. ‘There is such a tendency to exaggeration and inaccuracy in Irish reports that delay in acting on them is always desirable’, wrote Sir Robert Peel in 1845. By 1847 the description had changed: ‘Bodies half-eaten by rats were an ordinary sight; “two dogs were shot while tearing a body to pieces.” ’

The news of the coming famine might not be announced with sufficient clarity. Famines tend to be back-page news nowadays, perhaps for the very reason that they are too common to be worth mentioning. Although Ó Gráda speaks of ‘making famine history’6, the reality is that between 70 and 80 million people died of famine in the twentieth century, far more than in any previous century4.

The above predictions can be nothing more than approximate, of course, but even the most elaborate mathematics will not entirely help us to deal with the great number of interacting factors. We need to swing toward a more pessimistic figure for humanity’s future if we include the effects of war, disease, and so on. The most serious negative factor will be largely sociological: To what extent can the oil industry maintain the advanced technology required for drilling ever-deeper wells in ever-more-remote places, when that industry will be struggling to survive in a milieu of social chaos? Intricate division of labor, large-scale government, and high-level education will no longer exist.

On the other hand, there are elements of optimism that may need to be plugged in. For one thing, there is what might be called the ‘inertia factor’: the planet Earth is so big that even the most catastrophic events take time for their ripples to finish spreading. An asteroid fragment 10 kilometers wide hit eastern Mexico 65 million years ago, but enough of our distant ancestors survived that we ourselves are alive today to tell the story.

Somewhat related, among optimistic factors, is the sheer tenacity of the human species: we are intelligent social creatures living at the top of the food chain, in the manner of wolves, yet we outnumber wolves worldwide by about a million to one; we are as populous as rats or mice. We can outrace a horse over long distances. Even with Stone-Age technology, we can inhabit almost every environment on Earth, even if most of the required survival skills have been forgotten.

Specifically, we must consider the fact that neither geography nor population is homogeneous. All over the world, there are forgotten pockets of habitable land, much of it abandoned in the modern transition to urbanization, for the ironic reason that city dwellers regarded rural life as too difficult, as they traded their peasant smocks for factory overalls. There are still areas of the planet’s surface that are sparsely occupied although they are habitable or could be made so, to the extent that many rural areas have had a decline in population that is absolute, i.e. not merely relative to another place or time. By careful calculation, therefore, there will be survivors. Over the next few years, human ingenuity must be devoted to an understanding of these geographic and demographic matters, so that at least a few can escape the tribulation. Neither the present nor future generations should have to say, ‘We were never warned’.

Peter Goodchild is the author of ‘Survival Skills of the North American Indians’, published by Chicago Review Press. His email address is: prjgoodchild@gmail.com

REFERENCES:

1. BP Global Statistical Review of World Energy. Annual. http://www.bp.com/statisticalreview

2. Catton, William R., Jr. Overshoot: The Ecological Basis of Revolutionary Change. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1982.

3. Devereux, Stephen. “Famine in the Twentieth Century.” IDS Working Paper 105. www.dse.unifi.it/sviluppo/doc/WP105.pdf

4. Ó Gráda, Cormac. “Making Famine History.” Journal of Economic Literature, March 2007.http://www.ucd.ie/economics/research/papers/2006/WP06.10.pdf

5. Salisbury, Harrison E. The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press, 2003.

6. Woodham-Smith, Cecil. The Great Hunger: Ireland 1845-1849. New York and Evanston: Harper & Row, 1962.

7. Donella Meadows, Jorgen Randers, Dennis L. Meadows and William W. Behrens III. The Limits to Growth. New York: Universe Books, 1972.